Do cats have emotions? Do cats have feelings? Although the words emotions and feelings are often used interchangeably, emotions strictly refer to neurological responses to an event. Feelings on the other hand, are a conscious recognition of these physical sensations; feelings are generated from our thoughts.

Do cats have emotions? Do cats have feelings? Although the words emotions and feelings are often used interchangeably, emotions strictly refer to neurological responses to an event. Feelings on the other hand, are a conscious recognition of these physical sensations; feelings are generated from our thoughts.

do cats have emotions? Do cats have feelings?

Neuroscience shows that all mammals experience 7 basic emotions: SEEKING, RAGE, FEAR, LUST, CARE, PANIC/GRIEF and PLAY. Cats being mammals certainly experience these. But do they respond like we do to emotions? There will be differences in the types, durations and intensities of feelings experienced by cats and humans. We can’t know exactly what cats feel but we certainly can observe the emotional event and see whether it results in a positive or negative response.

“…affective neuroscience strategies now provide the needed “weight of evidence” indicating that animals do “feel” although, admittedly, we cannot be very precise about the experienced nature of their feelings, above and beyond several distinct forms of good and bad emotional feelings” (Reference 1).

How does this affect how we treat our cats? Traditionally, animal welfare has been focused on negative states such as pain and suffering, with the goal of keeping animals healthy and treating illness. This one-sided approach ignores the importance of positive experiences and emotions on health and longevity (Reference 2).

Recognizing Positive and Negative Emotional States in Your Cat

We can recognize positive and negative emotional states by observing cats’ body posture and facial expressions. These can be challenging to sort out. A cat with half-closed eyes may be painful, fearful or starting to relax.

Actions sometimes give us a better idea of what a cat is feeling. “Obviously, we can only ask if animals experience something by seeing if such states matter to animals. Will they choose to turn these states on or off? Will they return to or avoid locations where such states were artificially evoked (conditioned place preferences and aversions)?” (Reference 1).

If a cat approaches and rubs against you, he has made a choice to come to you. Presumably, his emotional state is positive. In contrast, when you bring the cat carrier out, your cat may hide, choosing to avoid the negative emotional state associated with going in the car to the veterinarian.

Do cats have emotions? opportunities for positive emotional states

Research conducted at the Battersea Dogs and Cats Home tested a simple set of guidelines (CAT) that aims to make cats more comfortable when they are interacting with us (Reference 3).

C – Allow a cat to CHOOSE whether or not to interact with you

A – Pay attention to the cat’s body language and behavior

T – Think about where you are touching the cat

C is for CHOICE:

Provide cats the opportunity to exercise some control over their environment and make pleasurable choices when possible. For example, if you need to move your cat, consider using a target or some treats to direct them to another place instead of picking them up.

A IS FOR ATTENTION:

How we handle animals has direct consequences on their welfare. Pay attention to to your cat’s body language when handling them. Get your cat’s attention before interacting with them. Start with a brief interaction and see how your cat responds. If they accept it, go for a bit longer. Be attentive to your cat wanting to end the interaction – turning their head or moving way from you.

T IS FOR TOUCH:

Consensual touch between individuals can communicate safety; such touch activates neurotransmitters such as oxytocin and ultimately dopamine. Oxytocin and dopamine are primarily associated with positive emotions, thus social touch is rewarding to the participants (Reference 4).

Friendly cats usually prefer being touched at base of their ears, around their cheeks, and under their chin. Watch for signs that your cat is done with being touched.

Collaborating with your cat

We can go one step further with these guidelines – start a conversation with your cat. Studies have shown that cats recognize their owners’ voices and learn the names of their companion cats. A recent study found that cats associated verbal words with pictures faster than human infants (8-14 months old). This study suggests that like apes, parrots and dogs, cats can learn human vocabulary (Reference 5).

Vocabulary for Your Cat

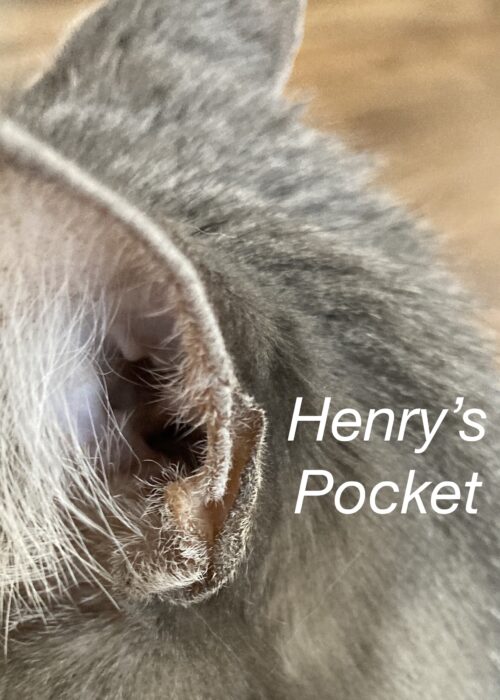

It is useful for your cat to know the words for the parts of his body, particularly those that may be touched. My cats learned the words “head”, “chin”, “cheeks” and “back” in 2-3 sessions. This allows you to ask, “Can I pet your head?”, giving the cat the choice to accept stroking to the head or to avoid it by turning their head aside.

Do cats have emotions? feelings?

Do cats have emotions? Feelings – the answer is yes.

In James Cameron’s movie “Avatar”, the sapient inhabitants of the planet Pandora, the Na’vi, greet each other with the phrase “I see you”. In the movie, this simple phrase is more than just physically seeing the person in front of you – it is also a spiritual kind of seeing – recognizing, seeing into, and understanding each other.

Your cat can learn much more than names of the parts of their body – they can learn to collaborate in their medical and physical care and become a treasured and valued companion. But, first, you must “see” them as having emotions, and able to mentally process (think about) those emotions, to have feelings.

references

- Panksepp J. Cross-species affective neuroscience decoding of the primal affective experiences of humans and related animals. PLoS One. 2011;6(9):e21236. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021236. Epub 2011 Sep 7. PMID: 21915252; PMCID: PMC3168430

- Browning H, Birch J. Animal sentience. Philos Compass. 2022 May;17(5):e12822. doi: 10.1111/phc3.12822. Epub 2022 Mar 17. PMID: 35859762; PMCID: PMC9285591

- Haywood C, Ripari L, Puzzo J, Foreman-Worsley R, Finka LR. Providing Humans With Practical, Best Practice Handling Guidelines During Human-Cat Interactions Increases Cats’ Affiliative Behaviour and Reduces Aggression and Signs of Conflict. Front Vet Sci. 2021 Jul 23;8:714143. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2021.714143. PMID: 34434985; PMCID: PMC8381768.

- Ellingsen Dan-Mikael , Leknes Siri , Løseth Guro , Wessberg Johan , Olausson Håkan. The Neurobiology Shaping Affective Touch: Expectation, Motivation, and Meaning in the Multisensory Context. Frontiers in Psychology, Vol. 6, 2016, http://10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01986

- Takagi, S., Koyasu, H., Nagasawa, M. et al. Rapid formation of picture-word association in cats. Sci Rep 14, 23091 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-74006-2)

Unlike humans, who can place an inhaler between their lips, and breathe the medication in, the coughing cat with asthma, like young human children, must inhale the medication from a chamber.

Unlike humans, who can place an inhaler between their lips, and breathe the medication in, the coughing cat with asthma, like young human children, must inhale the medication from a chamber.