Social Groups of cats in the multi-cat home

This post was originally published 8/29/20. This newer version has been edited to incorporate new material and references.

If there is plenty of food around, free-roaming cats tend to form groups called colonies. The core of the cat colony are the females, typically a mother, her sisters, and her daughters. These females share the care of the kittens – they nurse each others’ kittens and even help each other give birth.

Male kittens are driven off by their mothers at maturity to avoid inbreeding. They can become solitary hunters like their wildcat ancestors or become attached to an unrelated colony if accepted by the females.

Smaller social groups of cats often form within the larger social group of the cat colony. These groups of 2 or more cats typically

- sleep snuggled together

- groom each other

- rub against each other

- “play fight”.

These cats are comfortable sharing resources: food, water, litter boxes, sleeping and resting places. Often these are cats that grew up together but that is not always the case.

social groups of cats indoors -managing the multi-cat home

In the multi-cat home, some cats also prefer to stay together. Identifying the social groups of cats in the home can aid in allocating resources and reduce conflict among the resident cats [Reference 1].

Identifying the social groups of cats

Members of the same social group may

- sleep snuggled together

- groom each

- rub against each other

- engage in mutual social play.

There are no hard and fast rules to affiliation: some cats will not snuggle together, but will groom each other and play together.

A Multi-Cat Household and its Social Groups

Social Group 1

Athena forms her own social group. She is a 15 year old spayed female. She recognizes her housemates but prefers to spend time by herself or with her owners.

Social Group 2

Marley (14 yr neutered male) will hang out with 4 year old Zelda. They will rest together and “share” snacks. They will occasionally “play fight”.

Social Group 3

Zelda and Gus (3 yr old neutered male) groom each other’s heads and play together occasionally.

Gus and Zelda also go on walks together with their owners.

Allocating resources in the multi-cat home to reduce conflict

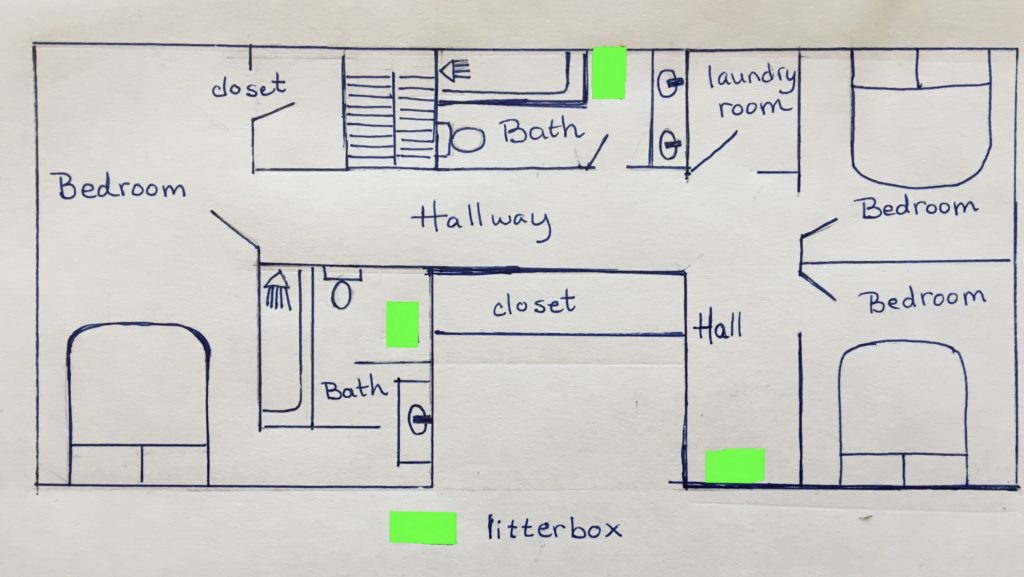

One of the keys to harmony in the multi-cat home is to provide multiple resources and spread them throughout the house. The goal is to ensure that all cats have access to litter boxes, food and water without having to compete with another cat. Here is a simple diagram showing the location of litter boxes on the second floor of a multi-story home [Reference 1].

When locating resources, watch for “bottlenecks” such hallway doors where cats may have to pass each other. Try and place litter boxes, water stations… away from these areas.

tips for managing resources in the multi-cat home

- # litter boxes = # social groups + 1

- Feed cats individually and out of sight of each other.

- Have daily play time for each cat

- Have multiple sleeping, resting places – have secluded and elevated choices

monitoring interactions between cats to manage conflict

Once the social groups in the house are identified, it important for the cat owner to monitor how the cats are getting along and intervene, if necessary, to prevent conflict [Reference 1].

- A cat fight can result in injuries to the fighting cats and the humans who try and manage the fight.

- Aggression does not need to cause physical injury – psychological stress resulting from one cat guarding resources from another can result in illness and undesirable behaviors such as house-soiling.

signs of conflict – signs of play

It is important to be aware of potential conflict in the multi-cat home. Signs of conflict not only include chasing, running away, howling and hissing, but also more subtle, seemingly harmless behaviors such as staring and blocking doorways. To make things more confusing, chasing and running away can be play behaviors! For more information, visit “How Do Your Cats Get Along – Conflict Behaviors”.

Cats are socially flexible and can form social groups with unrelated cats, although the strength and intensity of these social bonds can vary. A few aggressive interactions between cats who sleep snuggled together, groom each other and share resources may not point to a deterioration in their relationship [Reference 2]. However, cats whose affiliation is weaker and whose inter-cat interactions are frequently punctuated with hissing and growling may warrant a call to your veterinarian or a cat behaviorist.

The next post, “Managing Aggression in the Multi-Cat Home“, will look at identifying aggressive behaviors in more detail and what interventions are available to the cat owner.

references

- Ramos D. Common feline problem behaviors: Aggression in multi-cat households. Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery. 2019;21(3):221-233. doi:10.1177/1098612X19831204

- Gajdoš-Kmecová, N., Peťková, B., Kottferová, J. et al. An ethological analysis of close-contact inter-cat interactions determining if cats are playing, fighting, or something in between. Sci Rep 13, 92 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-26121-1

Want to keep up with the world of cats? Subscribe to The Feline Purrspective!

10,000 years ago, the ancestors of our domestic cats decided to take advantage of the abundance of prey near and in human settlements. During this time, the social lives of cats changed from solitary hunters to members of structured, stable groups called colonies. Today’s free-ranging cats, particularly those that live in urban environments, depend on food provided by people, in addition to hunting rodents and raiding human garbage cans.

10,000 years ago, the ancestors of our domestic cats decided to take advantage of the abundance of prey near and in human settlements. During this time, the social lives of cats changed from solitary hunters to members of structured, stable groups called colonies. Today’s free-ranging cats, particularly those that live in urban environments, depend on food provided by people, in addition to hunting rodents and raiding human garbage cans.

Cats don’t have to be “preferred associates” to choose a spot in the sun in the same room as a housemate cat. As long as there is plenty of space, peaceful coexistence should be possible.

Cats don’t have to be “preferred associates” to choose a spot in the sun in the same room as a housemate cat. As long as there is plenty of space, peaceful coexistence should be possible.

A human caregiver cannot replace a kitten’s mother – after all, we are not cats. For example, how does a human foster mimic the frustration accompanying weaning that encourages the kitten to get his own food? Kittens raised without their mothers and siblings are prone to behavioral issues – they don’t know how to deal with frustration; early separation from the mother may cause

A human caregiver cannot replace a kitten’s mother – after all, we are not cats. For example, how does a human foster mimic the frustration accompanying weaning that encourages the kitten to get his own food? Kittens raised without their mothers and siblings are prone to behavioral issues – they don’t know how to deal with frustration; early separation from the mother may cause