This post was originally published on June 20, 2021. It has been updated to reflect recent trends and changes in animal training.

The other day I was walking with Gus around the pond on the condo property. A neighbor came down the path – Gus approached him with his tail up, in greeting. The neighbor did not reciprocate but instead stopped a few feet away from Gus. Gus sat down and stayed still. The neighbor then walked by and muttered “ typical cat” as he passed by.

The neighbor clearly did not understand the tail up greeting. I wondered what he expected from Gus – was Gus supposed to come over wagging his tail? Gus approached with his tail up in friendly greeting. When the greeting was not returned (the neighbor did not offer his hand or get down on Gus’s level), Gus sat, and tried to figure out where the interaction was going – was it hostile or neutral? It certainly was not friendly.

In the past few decades, cats have increased in popularity as pets. Consequently, cat behavior and cat care have become popular subjects to study. We have learned that cats are social animals and can be trained. The stereotype of the aloof, antisocial cat is starting to change. We are starting to change how we think about cats.

Change how we think about cats

Cats – Mysterious? Aloof?

Indeed, we are more familiar with dogs’ body language than that of cats. People see dogs as more social than cats. Someone getting a puppy will plan to take it places, walk it and play with it.

Indeed, we are more familiar with dogs’ body language than that of cats. People see dogs as more social than cats. Someone getting a puppy will plan to take it places, walk it and play with it.

Kittens often stay at home and don’t venture out into the outside world – we don’t have to walk them; after all they have litter boxes. Once the kitten grows into a cat, people often don’t “play” with her that much – after all she is getting older and seems to sleep most of the time.

Dogs are viewed as more social than cats but recent research reveals that dogs and cats are similar in sociability. Cats are found to spend as much time with people as do dogs and the distribution of sociability in cats is similar to that found with dogs. (Reference 1).

There are some cats and dogs who are very social, spending most of their time with people. There are also cats and dogs in between, spending some of their time with people. At the end of the spectrum, there are cats and dogs who spend little or no time with people (Reference 1).

Cats – social and trainable

In the past few decades, cats have increased in popularity as pets. Consequently, cat behavior and cat care have become popular subjects to study. We have learned that cats are social animals and can be trained. The stereotype of the aloof, antisocial cat is starting to change. We are starting to change how we think about cats.

Dog training is shifting from traditional obedience to a cognitive approach by focusing on the dog’s thought processes, emotions, and problem-solving skills, rather than just rote memorization. This type of interaction is also appropriate for cats.

One way to engage a cat in conscious thought is through words and gestures. Studies have shown that cats recognize their owners’ voices and learn the names of their companion cats. A recent study found that cats associated verbal words with pictures faster than human infants (8-14 months old). Like apes, parrots and dogs, cats can learn human vocabulary (Reference 2).

teaching vocabulary – name & explain (Reference 3)

It is useful for your cat to know the words for the parts of his body, particularly those that may be touched. My cats learned the words “head”, “chin”, “cheeks” and “back” in 2-3 sessions. This exercise engages the cat in conscious thought and can be handy if, say, you’re going to comb the fur on his back. You say “ I want to comb your back”, and count to 3 before starting the groom. The cat knows what to expect and is less likely to startle or run away.

If your cat is amenable to being touched, touch the body part and label it verbally – repeat 3 times. Then start to use the word – if the cat appear to understand, affirm their choice. If they don’t seem to know it, simply label it again. If you are working with a cat who is leery of being touched, consider using a touch stick and a food reward (see “Teaching Cats How to be Touched“).

A quiet revolution is happening – be part of it. Change how we think about cats. Start a conversation with your cat and the enjoy the company of a companion who is not aloof, not mysterious, not just a sofa ornament but an interactive, thinking animal.

references

- Mills, Kim I. (Host). (2024, February). What’s going on inside your cat’s head? With Kristyn Vitale, PhD (No 275), [Audio podcast episode]. In Speaking of Psychology.

https://www.apa.org/news/podcasts/speaking-of-psychology/cat-human-bond - Takagi, S., Koyasu, H., Nagasawa, M. et al. Rapid formation of picture-word association in cats. Sci Rep 14, 23091 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-74006-2

- Cover, Kayce. Talk To Me, A communication guide for people living and

working with animals. Synalia Imprints publication, ©2010 Kayce Cover, pp. 10-15

Want to keep up with the world of cats? Click the button below and subscribe to The Feline Purrspective!

The idea of being able to talk to animals appeals to many people. The famous Dr. Doolittle, the central character in a series of children’s books, preferred animals to people and was able to talk to animals in their own languages. Nowadays, there are people who bill themselves as animal communicators and will “talk” to your animal for a fee.

The idea of being able to talk to animals appeals to many people. The famous Dr. Doolittle, the central character in a series of children’s books, preferred animals to people and was able to talk to animals in their own languages. Nowadays, there are people who bill themselves as animal communicators and will “talk” to your animal for a fee.

Introducing a new cat to an established group of resident cats can be challenging. Most experts recommend a slow, gradual introduction, similar to how wild cat colonies accept new members.

Introducing a new cat to an established group of resident cats can be challenging. Most experts recommend a slow, gradual introduction, similar to how wild cat colonies accept new members.

In this post, we look at how cats get along with other species – are their behaviors affiliative or is there conflict?

In this post, we look at how cats get along with other species – are their behaviors affiliative or is there conflict? Cats use the same friendly behaviors when interacting with people as they do with other cats.

Cats use the same friendly behaviors when interacting with people as they do with other cats. A Tale of Tails

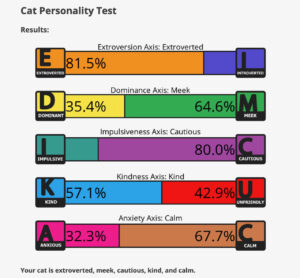

A Tale of Tails Do cats have personalities? If you

Do cats have personalities? If you