Pain is a response to injury and illness. It motivates an animal to protect the wounded part of the body or to slow down to allow the immune system to work. But at a certain point, pain may not be functional – for example, if an animal is too painful to eat. Managing the painful cat must reduce pain without inducing dysphoria – a state of unease and dissatisfaction (Meriam-Webster).

Cats are not only predators, they are also prey for larger carnivores like coyotes. A predator will target a weak or injured prey animal so it is important that prey animals hide their pain, so they don’t become some else’s snack. How do we recognize pain in a cat? How do we manage the painful cat?

Managing the Painful Cat

Managing the painful cat requires that:

- We recognize the pain and its severity.

- The veterinary team formulates a treatment plan, which includes pain medications and supportive treatments.

- The cat owner implements the plan, monitoring the cat’s pain and response to treatment.

Pain can divided into “acute” pain and “chronic” pain.

Acute pain (Reference 1):

- rapid onset

- short duration (3 months or less)

“Chronic” pain (Reference 1)

- occurs along with a chronic health condition

- longer duration

We will focus on “acute” pain in this article.

Some causes of “acute” pain are:

- surgeries: spay, neuter, dental extractions

- illness such as pancreatitis, infections

- bite wounds from a cat fight

How do you know if your cat is in pain?

Changes in behavior, posture, and temperament may be indicators of pain or illness. Some examples are:

Changes in behavior

- decreased appetite

- decreased grooming

- urinating or defecating outside the litter box

- sleeping in unusual places

Changes in posture

- hunched or crouching

- changes in gait: walking stiffly, limping

Changes in Temperament

- a typically friendly cat does not greet you and hides under the bed

- the cat is aggressive toward people or other animals

If you notice such changes, a visit to your vet is in order. Your vet may prescribe therapeutic and pain medication, suggest environmental changes and other supporting therapies such as warm or cold compresses. During the treatment and recovery period, it is important to monitor your cat and note her response to therapy:

- behavioral changes: is there improvement

- pain assessment

The Feline Grimace Scale (FGS) provides cat owners with a way of assessing acute pain. The FGS focuses on 5 features of the cat’s face: position of the ears, shape of the eyes, shape of the muzzle, attitude of the whiskers, and position of the head. The user assigns each feature a score of 0 (no pain), 1 (moderate pain), or 2 (obvious pain) for a maximum of 10 points. A score of 4 indicates that the cat is painful. To use the FGS, see https://www.felinegrimacescale.com/

The Feline Grimace Scale (FGS) provides cat owners with a way of assessing acute pain. The FGS focuses on 5 features of the cat’s face: position of the ears, shape of the eyes, shape of the muzzle, attitude of the whiskers, and position of the head. The user assigns each feature a score of 0 (no pain), 1 (moderate pain), or 2 (obvious pain) for a maximum of 10 points. A score of 4 indicates that the cat is painful. To use the FGS, see https://www.felinegrimacescale.com/

Effective pain management enhances healing and will help the cat return to its daily activities faster. Be sure to give medication as directed by your veterinarian. If you have difficulties administering medication or following other instructions, contact the vet clinic immediately for alternative ways of giving medication or other methods of providing supporting therapy. If you feel your cat is in pain in spite of the prescribed treatments, contact your veterinary team – perhaps another medication or therapy will be more effective.

“ It is reasonable to assume that anything that would cause us pain, will also cause pain in cats

and be just as distressing for them” (Reference 2)

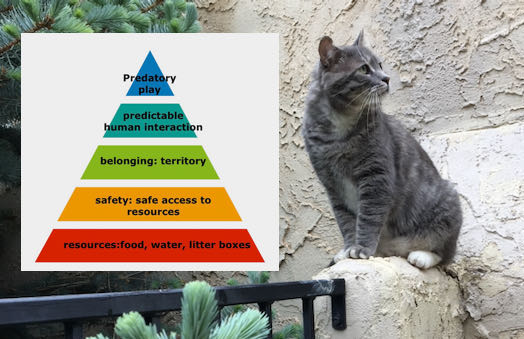

Managing the painful cat not only involves giving prescribed medication and treatments in a timely way, it also includes keeping the patient physically comfortable. Environmental modifications can help the painful cat return to the comfort of his daily routine.

Environmental Modifications to Help the Painful Cat Recover (Reference 2)

- Restrict outdoor access and activity as directed by your vet

- Provide options for quiet rest, ensuring the bed is in easy reach

- Essential resources – food, water, litter box and bed – must be close by. The recovering cat may not want to move very far.

- Encourage your cat to eat by offering palatable foods and warming them when appropriate, per your veterinarian’s instructions.

- Keep other pets and children away if they are likely to disturb the cat or, for example, disturb a bandage.

managing the painful cat: A Case History

In the autumn of 2021, I was taking my cat Gus on short hikes on a nearby mountain trail. One hike, he startled, I lost hold of the leash and he disappeared up the trail. After 2 hours of walking up and down the trail, calling for him, he appeared, without harness and leash, moving stiffly. I carefully put him in his backpack and took him to the vet clinic for an exam and x-rays.

The exam indicated that he had a lot of inflammation in his lumbar spine and was reactive to palpation of that area. X-rays did not show any injury to his skeleton.

We tried NSAID therapy, oral opioids and gabapentin, but there was little improvement in 3 days. Gus was so painful that he would growl when changing positions.

The next visit was to the neurologist in Denver for an MRI which showed inflammation but no obvious nerve damage. We added a steroid to his therapy; I also gave him twice daily red light therapy. Gus began to improve and recovered fully after 6 weeks.

environmental modifications

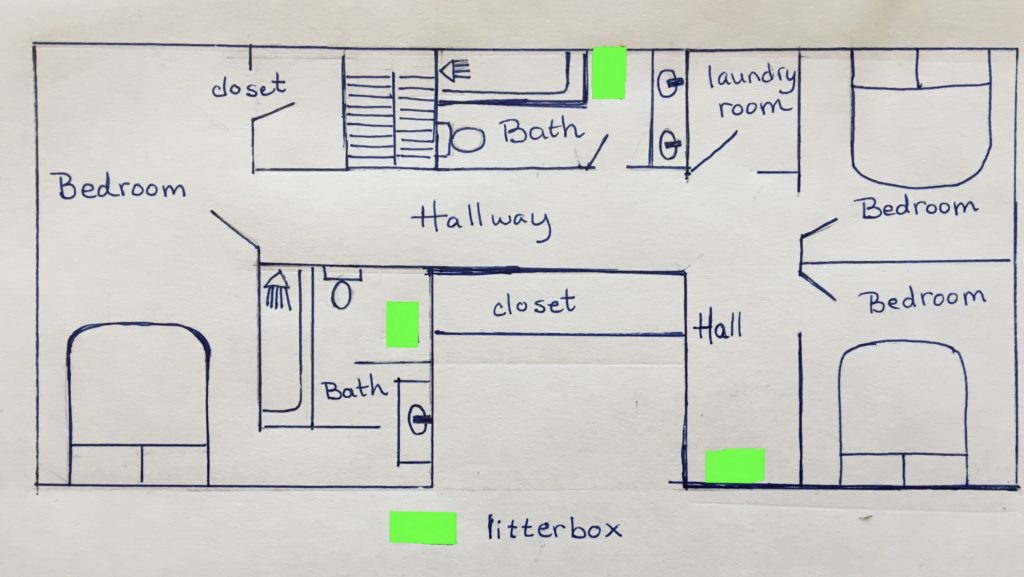

- Gus was set up in the master bath with the doors closed to keep other cats from entering

- A litter box with a low entrance was provided

- A bed made of blankets was placed on the floor

- A bowl of water was next to the bed

giving medications

- A decreased appetite precluded Gus voluntarily taking a pain medication in a treat

- Medication was administered using a squeeze up treat (see “How to Give Your Cat a Bitter Pill“)

the efficacy of pain medication and an environment conducive to healing

Although the “tincture of time” was an important factor in Gus’s recovery, alleviating pain and discomfort accelerated healing. The addition of prednisolone (a steroid) to the therapy helped reduce swelling in Gus’s spine – he began to move about more easily the day following his first prednisolone dose. The steroid also stimulated his appetite and having a bed on the floor with easily accessed litter box nearby encouraged elimination.

In the weeks that followed the hiking accident, Gus gained mobility although steps to access high places were still needed. At first, Gus was not able to hold his tail up but he recovered fully in the weeks that followed.

Managing the painful cat requires recognition of pain and a treatment plan from the veterinarian. After that point, the cat’s care is in the hands of his owner who must monitor him for pain, ensure that he eats and eliminates, and provide him with an environment conducive to healing.

references

- Steagall PV, Robertson S, Simon B, Warne LN, Shilo-Benjamini Y, Taylor S. 2022 ISFM Consensus Guidelines on the Management of Acute Pain in Cats. Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery. 2022;24(1):4-30. doi:10.1177/1098612X211066268

- Recognising and Managing Acute Pain in Cats:Information for Owners/Caregivers. https://icatcare.org/app/uploads/2022/02/Cat-Carer-Guide_Acute-pain.pdf viewed 3/2024

Want to keep up with the world of cats? Subscribe to The Feline Purrspective

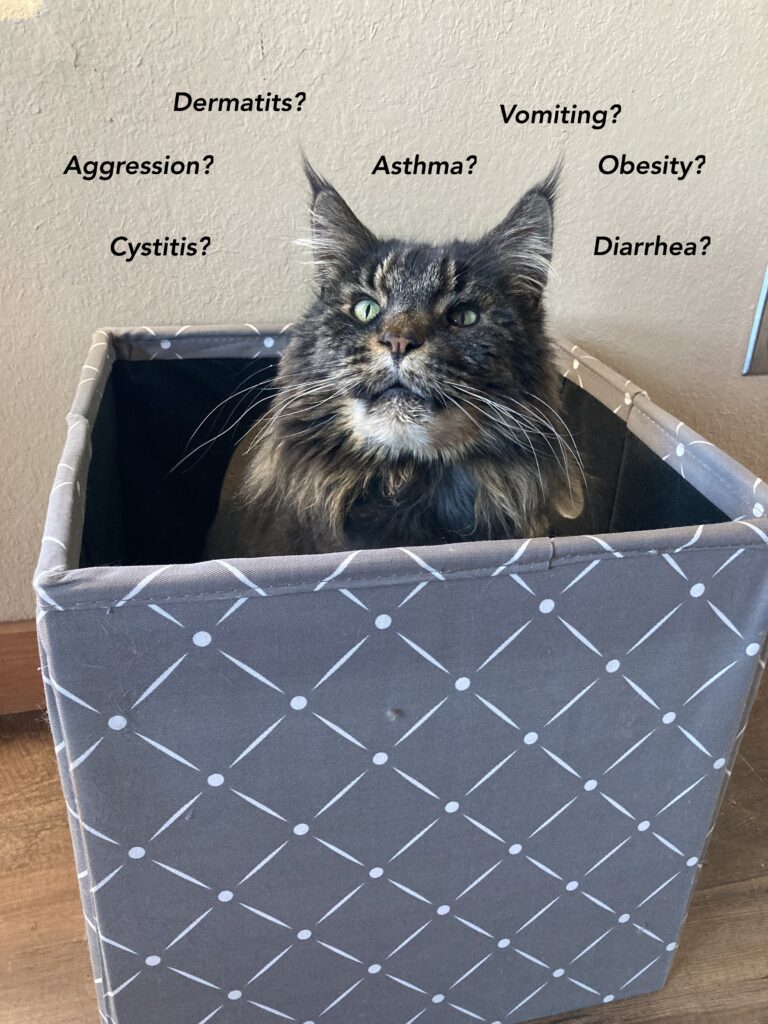

There has been a stray cat hanging around the house. He is friendly and after a few weeks of feeding him and scratching his head, you decide to adopt him. You do the responsible thing and take him to your vet for an exam, vaccines, and FeLV/FIV test.

There has been a stray cat hanging around the house. He is friendly and after a few weeks of feeding him and scratching his head, you decide to adopt him. You do the responsible thing and take him to your vet for an exam, vaccines, and FeLV/FIV test.

Treating Pandora Syndrome in cats: MEMO

Treating Pandora Syndrome in cats: MEMO